[00:00:12] Speaker A: Hi, my name is Geraldo Cadava, and I want to thank you for tuning into season three of Writing Latinos, a podcast from Public Books.

We're back for more terrific conversations with Latino authors writing about the wide world of Latinidad.

As always, we aim to provide thoughtful reflections on Latino history, culture, politics, and identity and how writing conveys some of its meanings.

Don't forget to like and subscribe to Writing Latinos wherever you get your podcasts. And now for the show.

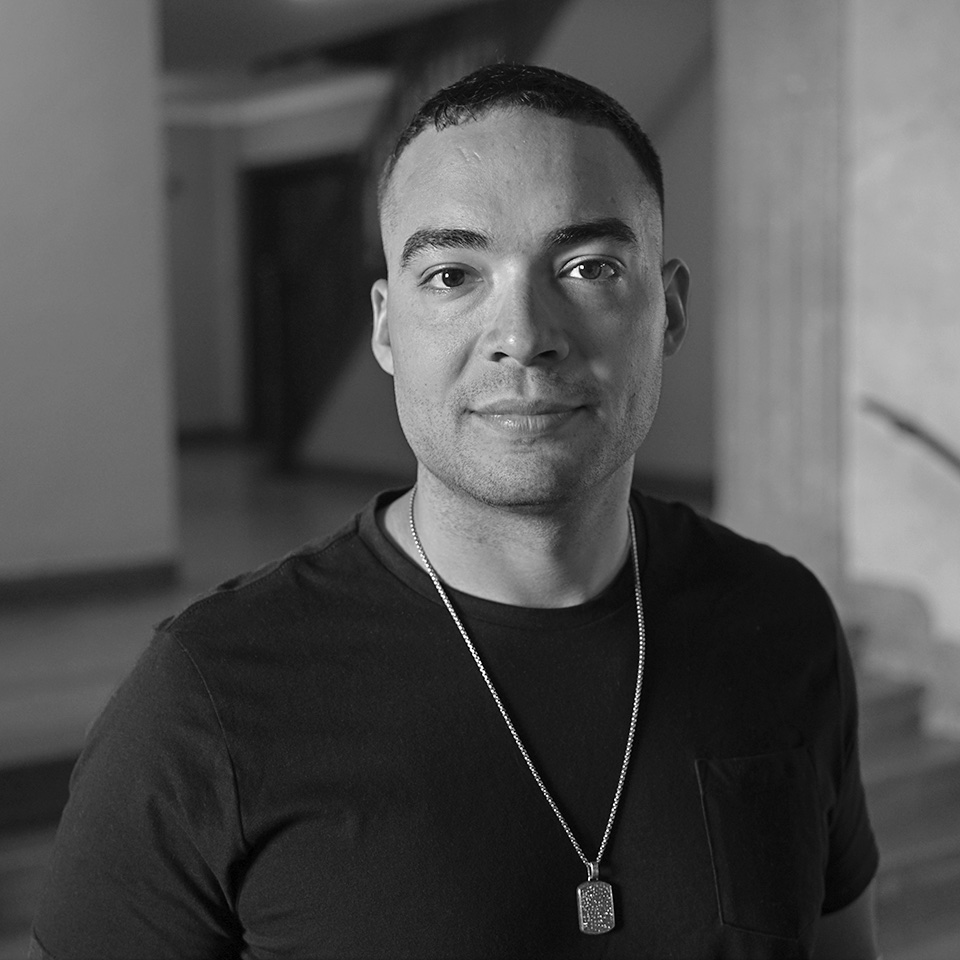

[00:00:49] Speaker B: Today, we're talking with Jorrel Melendez Badillo, who teaches Caribbean and Latin American history at the University of Wisconsin, Madison.

He's the author of two the Lettered Workers, Archival Power and the Politics of Knowledge in Puerto Rico, published by Duke University Press, and Puerto Rico A National History, published by Princeton University Press.

This second book was just released in paperback, and it's the book we're talking about today.

Late last year, Melendez Badillo also received a DM from Bad Bunny's team that led to a collaboration with Sanbenito himself. And of course, we'll talk about that, too.

So buckle up because this is going to be a good one.

We're so delighted to have Jorrel Melendez Badillo with us today, and thank you so much for joining us.

[00:01:39] Speaker C: Jor El thank you for having me. It's a great pleasure.

[00:01:43] Speaker B: Yes. So let's start with this amazing experience you recently had. We'll just jump right in and you helped Bad Bunny write some of the historical notes that accompany his new album, Debitirar Mas Photo. So, so first, can you just tell us how that came about? I imagine you getting like a cold call or an email from Bad Bunny, but tell us how that really happens.

[00:02:03] Speaker C: Yeah, absolutely. So I was not expecting it at all. I was actually traveling in Europe with my family over holiday break, and I got an Instagram message on December 24. Actually, I was added by three people in Instagram, and all of them were from the world of, like, art movies in Puerto Rico, which struck me as weird. And so I added them and I immediately got a DM from one of them, which identified as a producer for Limas, the production house of Bad Bunny. And so they asked me if I was interested in having a conversation about a potential collaboration with Benito. And I'm a huge fan. I had promised my wife, my kid, my therapist that I was going to leave my computer behind, so I had no computer, but I immediately said yes.

And so I got a call from the Bad Bunny team and they explained sort of the sensibility of the New record that it was tied to Puerto Rican history, highlighting Puerto Rican culture. They talked about the residency that he was going to do. They also mentioned the short film that was being developed to accompany the record. And so they explained that Bunny basically wanted history to accompany the visualizers, which is this. This way of artists monetizing out of YouTube. They basically add, like, short videos to their songs in YouTube, the ones that don't have music videos. And so instead of just having a normal. What they usually do, which is a short video, Benito wanted to amplify and highlight Puerto Rican history.

And so it was very exciting, but it was also a lot of work. As I said, I had no computer. I worked by hand. I basically wrote about 74 handwritten notes, or 74 pages of handwritten notes. And it was on December 24th, and it was due by January 1st, because the record was coming out on January 5th. So it was very rushed, but also exciting at the same time.

[00:04:03] Speaker B: That is wild. And wait a second. So did they tell you you wrote 74 pages, but did they tell you what subjects they wanted to write, wanted you to write about? Or was it.

[00:04:15] Speaker C: Yeah. So initially, the producers that told me that Benito was interested in the unknown history of Puerto Rico, they had read my book, People in the Team, So that's how they got a hold of me.

They basically imagined that the sensibility that I had in my book was sort of the same sensibility that Benito was portraying in the record. And so they wanted Puerto Rico's unknown history. So I wrote about 74 sort of ideas of unknown characters, very neat sort of individuals and characters in Puerto Rican history. And Benito came back and said, no, that's not what I want, because Puerto Rico's history is unknown generally. And so he wanted this sort of balance between general histories of Puerto Rico and more sort of focus histories. And so I was given a lot of liberty, creative liberty, in writing the topics.

But Benito was also very interested in particular things. Like, for example, he was interested in having the history of Puerto Rican repression throughout the 20th century. He also wanted the history of reggaeton tied to polena and bomba. He also wanted one on animals in danger of extinction. But they also allowed me to write about working class history, about women, about radical history. So it was this sort of balance between general history and more specific histories of Puerto Rico.

[00:05:39] Speaker B: That is amazing. That's so, so cool. Jor?

[00:05:42] Speaker C: El.

[00:05:42] Speaker B: And did you have the chance to talk with Benito himself?

[00:05:45] Speaker C: Yeah. So I was across the pond, so I was in Europe. And so we communicated via WhatsApp audio. I actually communicated with someone in the team, a producer, but he would forward me Benito's messages, audio messages, and I would reply with my own audio messages.

And so that was a way that we communic via a third person through WhatsApp, which is, you know, I. I like to joke, it's the most Latin American app ever created. And so it was very fitting. It was very fitting. But Benito was really interested in this history being read by people outside of academia. He actually, in one of the conversations, he told me that he was not interested or that this was not catering towards UPR students, University of Puerto Rico students, but to people in the projects and the working class neighborhoods y cacerio. So there was an intention behind the project of it being read outside of certain circles and to amplify and massify Puerto Rican history, which is very in tune with my own sort of ethos as a scholar. I was over the moon not only of being able to collaborate with Bad Bunny, which I'm a huge fan, but also of amplifying Puerto Rican history. And the last time I checked, the visualizers have more than 400 million views in total.

So it's beyond my wildest dreams.

[00:07:12] Speaker B: That's amazing.

[00:07:12] Speaker C: Absolutely. And a lot of people have said that this record actually sort of like a snapshot of the current political moment in Puerto Rico because it amplifies conversations around gentrification, displacement, you know, cultural affirmation. And so for me, yeah, absolutely. It's part of my own sort of scholarly archive that I'm creating.

[00:07:33] Speaker B: That's great. That's great. Maybe you can even write about it at some time. We'll see. But, you know, my last question on this subject before we turn to your book, which is what led his team to reach out to you in the first place? I wanted to know if the experience has kind of shaped or if you've drawn any conclusions, I guess, from this experience about how scholars participate in the production of popular culture and just communicate with broad audiences generally.

[00:08:01] Speaker C: I became a historian and an academic because I wanted to take the knowledge is produced within academia outside of the ivory tower.

Very ideally or naively, I could say I wanted to basically get those knowledges out. And so I really thought in my own scholarship that I was not doing a great job.

For example, when I published the letter Barriada, it's a book about working class histories and it was really tied to my own personal experiences growing up in a working class household, someone asked me, what did my grandparents think about it? The grandparents had actually made me write that book, and it was illegible to them. And so when I wrote Puerto Rico, I was really thinking about other audiences, how I had to unlearn a lot of things. And so working with Benito, it was a very challenging thing, not only because of the time crunch, but also because I needed to write to the broadest audience I had ever written to. And I had to synthesize and summarize very complex historical moments and ideas in a few words. And so for me, it was a challenge. And also, to answer your question more directly, I think that it really showed me that there is a desire to learn Puerto Rican history. There's a thirst for Puerto Rican history in Puerto Rico. And I think that this is part. I'm actually writing an essay reflecting on the reception of the book and of this thing that happened with Benito on the politics of forgetting in Puerto Rico, because I think that part of what happens in Puerto Rico is that history is not being taught in the classroom, because there is a politics of forgetting that is tied to colonialism and the ways that colonialism operates in Puerto Rico. And what I've learned from all of this is that there is a real thirst and a real desire to learn our histories, but it's inaccessible at times for people.

[00:09:59] Speaker B: Absolutely. I'm so glad to hear you say that. I mean, I've been working for the past few years with high school teachers here in the United States who are also kind of just hungry to have Latino history in their classrooms. And I think it's important for historians to figure out how they can, you know, disseminate that history, not necessarily to the masses. I mean, that would be good, but at least to the teachers who are teaching kids. You know, I think that's. That's great, and I'm glad that you've had the chance to do that. And it sounds like you're interested in continuing to do that.

[00:10:33] Speaker C: Thank you. Because I. I'm really eager. I.

I never thought of myself as a public historian, although that I. I.

A lot in Spanish. I published for my communities here in Puerto Rico. And that didn't count for my tenure file in US Academia, But I still did it because I thought it was important for me to be in dialogue with those communities in Puerto Rico. And I think that now this has given me another opportunity. As you were mentioning, I'm really interested in high school teaching. I was a high school teacher myself before becoming an academic, and I've gotten so, so many messages, not only from teachers, but also from students that are Consuming this information that Benito put forth in the visualizers. And so for me, it's been very mind blowing just to see that it's not only in the club, because I've gotten pictures of people periando and dancing in the club with Puerto Rican history in the background, but also that it's been used in classrooms not only in Puerto Rico, but also in the U.S.

[00:11:35] Speaker B: Okay, so let's dive into your book. You know, the. The original point of connection between you and Benito. Anyway, you wrote a book called Puerto Rico A National History. And that book is going to come out in paperback very soon. So it is, at least as I read it, it felt to me to be a provocation, even in the title, to claim to write a national history of Puerto Rico, because this is a place that hasn't been an independent nation for the better part of 500 years. So I'm wondering if you can explain what it means to think of Puerto Rico as a nation.

[00:12:13] Speaker C: Thank you for that. I think you captured it beautifully because I think that the book in itself was a provocation. The title, Puerto Rico National History. Originally the book was going to be titled Puerto Rico Five Centuries of Colonialism, Five Centuries of Resistance, which was an homage to Francisco Carano, a historian of Puerto Rico's book, Puerto Rico Cinco Ciglot, Five Centuries of History.

I thought that Puerto Rico and National History captured that sensibility that I originally wanted to have in the book, but it was also a provocation.

I was told not to read the comments in Facebook and I've done it, unfortunately. But there's a lot of debate around particularly the idea of the nation. And so I wanted to be provocative from the get go because I think that for me, calling Puerto Rico a nation is a form of affirmation in the face of 500 years of colonialism.

And so, yeah, so the book tries to cover this bass history of Puerto Rico, or the place that we now call Puerto Rico, from pre Columbian times to Bat Bunny, because the book ends with bad bunny, actually. But it is in itself a provocation, the title of affirming that although we've been colonized first by the Spanish and then by the United States, Puerto Ricans have dared to imagine themselves as another thing. They have created their own sense of. Of self. And ultimately they have created this idea of the nation that is fluid, legally ambiguous and diasporic, which is something that I was really.

That I really wanted to bring into the ways that we conceptualize the Puerto Rican nation, historiographically speaking.

[00:14:06] Speaker B: And if it's not too triggering for you, Jor? El, I'm wondering if you can tell us what some of the reactions on Facebook were. Not for any kind of salacious reasons, but just because I think the reactions are probably representative of the contours of the debate. So when you say that Puerto Rico is a nation and should be understood as such, what are the reactions to that?

[00:14:33] Speaker C: Part of the reaction has been very polarizing in terms of a lot of people saying that Puerto Rico is not a nation, that Puerto Rico is a commonwealth, which is factual. But I think it misses sort of the nuances of the relationship between Puerto Rico and the United States. Other people say that it's not a nation, that it's a territory. And so it's part of this broader debate in Puerto Rico, this ongoing sort of very long standing debate about the political status of the island in terms of its relation to the United States. Some people want it to be a state of the union, others want it to be autonomous, as it is as a commonwealth, and others want it to be independent. And I think in the independent camp, you can see that they understand Puerto Rico as a nation. But one of the things that I argue in the book is that when you look at the history of modern Puerto Rico, those three factions, all of them imagined Puerto Rico as a nation. It meant different things to different sectors.

But I think that what I saw in the comments, the thing is that in the comments, it's more crude. People are trashing other people, they're swearing and cursing at each other, which I think it's very telling of how deeply ingrained the question of the political status in Puerto Rico is.

And I think that that's important because ever since the creation of modern Puerto rico In the mid 20th century, the political status has been at the center of the political and electoral debate.

I just wanted to be provocative and say that Puerto Rico is a nation.

Also, on the other hand, the book, I don't think it's a book about the Puerto Rican nation.

It is a book of how different social groups have imagined the nation.

A lot of people tell me congratulations on writing this nationalist history of Puerto Rico, but it's not a nationalist history. It's basically historicizing the idea of the nation. For me, it's even more interesting because it's historicizing the idea of the nation in a colonial space that has never achieved the status of a nation state in the 19th century Western imaginary of what a nation state should be.

[00:16:55] Speaker B: Yeah, that's so fascinating. You know, last week I just read for the first time, embarrassingly, Jesus Colon's vignette called A Puerto Rican in New York. And it says something like, you know, you guys don't even realize how close we are to independence. And it's funny because it's a story, you know, written in the mid 20th century at some point. And in the story he's kind of actually reflecting on the fact that not much has changed in the past 40 years. And I read it in 2025 and heard him say, you know, you don't know how close we are to independence. And I thought, like, oh, well, you know, that hasn't happened either. And to me, I don't even know if he literally meant that he thought Puerto Rico was about to become independent. But it's another example of thinking about Puerto Rico as a nation, an independent nation, even in the context of colonialism. So I like that, that tension there.

[00:17:49] Speaker C: And one of the things that I was really cautious when writing the book is that in the mid 20th century century, the state, particularly led by El Partido Popular Democratico, the Popular Democratic Party, basically created the foundations of modern Puerto Rico. And one of the tenets of this modern Puerto Rico was this idea of cultural nationalism that we could think of Puerto Rico as a nation detached from the political status of the archipelago. I was really cautious not to reproduce those logics of cultural nationalism that were tied to that nation building process. But I think it goes back to this moment that you're mentioning with Jesu Colon, because it shows how even in working class diasporic sectors, they're thinking about the political status of Puerto Rico. And it's such a pressing question, even if it's in New York, in Kissimmee, in Madison, or in Santurce, Umacao or Aguadilla. And so it's at the heart of how people imagine Puerto Rico and its future. So I think it's a future oriented question, right? And I think when I think about Puerto Rico's history, for me, I see it as a future oriented history of where are we going to move forwards, towards. And not in a teleological, Eurocentric way, but the colonial condition forces us to grapple as Jesus Colon or Bernardo Vega did in the early 20th century today. And as you mentioned, we could read Jesu Colon Orega and all those sort of working class intellectuals and their ideas about the political status of Puerto Rico in 2025.

And it feels fresh and new because it's still part of the ongoing political conversation.

[00:19:43] Speaker A: Writing Latinos is brought to you by public books, an Online magazine of ideas, arts and scholarship. You can find

[email protected] that's P U B L I C B o o k s.org to donate to public books.

[00:20:00] Speaker B: Visit publicbooks.org donate it's so interesting that you described your book as future oriented because in order to orient your book toward the future, you felt the need to go back more than 500 years in time. And that's interesting. So I think the decision to do that also comes at a moment when writing sweeping histories is kind of back in fashion after decades, when it wasn't when we were looking at particular moments, particular communities, particular aspects of communities. And so I'm thinking about books like Ada Ferrer's book Cuba An American History. I'm thinking of Greg Grandin's new book, America America. And so these are examples of sweeping histories of the Americas, parts of the Americas. And so I'm wondering, why did you feel the need to go back to the beginning to explain Puerto Rico and to orient Puerto Ricans today toward the future?

[00:21:09] Speaker C: Well, two things. The first thing is that when I was writing the book, I was thinking about Ricardo Piglia once said, or I heard him say once, that writing is a form of plagiarism of that which you have read in the past.

And so I. I consciously did not read ala's book when it came out until I finished mine because I didn't want to copy Ada and I knew it was going to be a brilliant narrative of Cuban history as it is. Right. Well, deserving of all the awards. And I haven't read Grandinc's book because it just came out, but I cannot wait to read it.

But I consciously did not read ALA because I wanted to approach Puerto Rican history in my own sort of conception.

The second thing I would say is that I was not planning on writing this book so early in my career. I was actually trying to pitch another book to Princeton to my editor, Priya Nelson, who is an incredible editor and individual and human being. I was trying to pitch a book on anarchism, which is a book that I'm currently writing and it's under contract with Duke University Press.

And Priya came back and said, that sounds great, sounds interesting, but I'm more interested in a history of Puerto Rico. Would you be willing to write such a history?

I come from a working class background, and when you see an opportunity on the table, you take it and then you think about what you just agreed to.

I said yes, and it was a pandemic project.

I really wanted to think about my own condition as a diasporic Puerto Rican subject. And so I used this sort of.

This opportunity to reflect on my own positionality, to think about the role of the diaspora, and also to understand how we got to the current political moment. You know, we are in a moment of ongoing crisis in Puerto Rico. We're going to hit next year two decades of an economic recession, depression, an ongoing crisis, crisis on a social, economic, you could say, even spiritual level in Puerto Rico. So I wanted to understand how we got to that moment. And so in order to do that, I wanted to begin the history with pre Columbian societies. And also by doing so, I wanted to decentralize certain dates and individuals. I wanted to decentralize 1493, and instead I begin with pre Columbian societies. And then sort of the major moment in chapter one is this insurrection in 1511.

And along the way to chatter certain myths that I was taught in school. And so I think it's an interesting moment, this moment of sort of narratives, of these sort of national narratives, sweeping narratives.

And I think there's some usefulness there, right? And it all depends on how we read them and how we write them. And I think about Jack Rancier, and he has this comment on Braudel's El Mediterraneo, the Mediterranean, in which Transier notes, Braudel only mentions a king in the last page of this sweeping history.

And so I was also inspired by that. What does it mean to write sort of this quote, unquote, national history of Puerto Rico from the margins, decentralizing certain dates and moments, and also thinking about my own subjectivity and how we got to this political moment. And so that's why the book doesn't begin with heads of states. It begins with my grandparents.

And also it's a process of reflecting about the current political process in Puerto Rico.

[00:25:04] Speaker B: So much of what you said is really interesting and resonates. First of all, just I love the story about your editor kind of turning back your idea, at least for the moment, to ask you to write a broader history of Puerto Rico. Because one of the stories that Greg Randon tells in America, America is how he had started talking to his editor. He was ready to pitch his editor this book about the Monroe Doctrine. He wanted to start with the history of the Monroe Doctrine and how it's been invoked over the past couple of hundred years. But his editor said the same thing. She was like, well, I think you actually need to go back to the Spanish conquest. And so, so good on editors. You know, I mean, editor is trying to understand this bigger picture, But I also, you know, I do think I'm. I'm thinking a lot about similar questions, in part because I'm writing history of Latinos over the past 500 years. But why? You know, I think that will also be part of these larger reframings of American history, timed to these broader national conversations about what it means to be celebrating the 250th anniversary of the United States. But I also found it interesting that you talked about a moment of crisis as an opportunity to tell these sweeping narratives. And I've been thinking about how, you know, when things. When things feel very broken and we don't understand them, that, to me, seems like the perfect moment to say, you know, I think we need to go all the way back to the beginning to try to understand what has happened. So I think. I think there's something there about thinking about moments of crisis as opportunities to go back to the beginning.

[00:26:45] Speaker C: I completely agree. And part of what drives my own thinking is this idea of ruptured memories. And this is idea I borrow from Puerto Rican scholar Arcadio de Aquinones, The Goat, I like to call him.

Arcadio de Aquinones has this beautiful essay that he published in the early 90s called La Memoria the Ruptured Memory. He argues that in modern portraits, one of the things that the state did was that it broke away with collective memories and instilled new sort of collective memories from the state, using a newly created archive system, a newly reformed university, the creation of a grassroots educational program. And I really think that in this moment of crisis that began in 2006, the state once again broke away from collective memories, but it doesn't have the capacity to instill a new collective memory. And so I think that in the case of Puerto Rico, there's a real sense of urgency in cultural and intellectual work. And that's why I think that as you were saying, in these moments of crisis, it's so important to go back to the beginnings, to understand how we got to this moment. And I think that in the case of Puerto Rico, there isn't sort of a collective memory. There are multiple competing collective memories or memories that are being developed. And so I wanted my book to be part of that ongoing conversation of how do we think about ourselves? And one thing that for me is also very interesting is that the case of Puerto Rico, because of its colonial condition, doesn't offer us a beginning, a clear beginning, or a clear end. And so it's this continuum of this sort of colonial relationship that allows us to go back and forth in time as we narrate the history of Puerto Rico. And so, yeah, I think that moments of crisis and in Puerto Rico, particularly this ruptured memory and this sort of politics of forgetting are crucial for me in having this book published in this particular moment. And, you know, for the histories of Latinos in the United States, which I cannot wait to read the book that you're writing. You know, it is a moment of deep crisis as well, because of all that's happening in the United States.

[00:29:10] Speaker B: That's right. And I think that your book, you know, it is trying to actually restore or rebuild a collective memory. But it is a very different vision of collective memory and an effort against the forgetting you're talking about than what has been tried in Puerto Rico in the past. I mean, you describe this moment in the 1930s when I don't actually remember who the main protagonists were, whether it was elite intellectuals or who, but they tried to create this collective history of national Puerto Rican identity as very tied to Spain. And Puerto Rico is Spanish, and it was the Spanish past that was the important past that Puerto Ricans needed to remember. So I think that you're trying to tell a very different story about the collective history of Puerto Rico. And, you know, I did think that there was this tension between what you describe as many Puerto Ricos. And I liked that a lot because I remember sitting in on Gil Joseph's undergraduate lectures on Mexican history, and his first lecture was about Muchos Mexicos, you know, and he was walking, walk students through the various regions, the south and north, how they were different. But your many Puerto Ricos, it wasn't just based on kind of geographic diversity. It was about workers and elites and indigenous and Spanish, urban, rural and the diaspora and those who remained on the island. So it felt to me like there was this tension between many Puerto Ricos and this desire in the early 20th century to tell a more homogenous story about Puerto Rican national identity as Spanish. And I'm wondering if those two different visions of what the Puerto Rican nation is, either this kind of collection of many Puerto Ricos or a more homogenous Puerto Rican national identity as Spanish, are those two ten, two kind of polar opposites in a lot of ways? Are those perpetually in tension, or do you think there's a way to resolve those different versions of national history?

[00:31:26] Speaker C: I really, really, really appreciate this question, because part of what the book is trying to do is to challenge this notion of Puerto Rican docility that was articulated by a certain intellectual group in Puerto Rico with deep ties to that intellectual generation that you're describing, led by people, professors at the University of Puerto Rico, such as Thomas Blanco, Antonio SE Pedreira, people that were instrumental in setting the foundations of the idea of Puerto Ricanness that the state. State will appropriate in the 40s and 50s and it will become part of the state narrative. And so for them, this was a political and intellectual class that was disenchanted with the US colonialism and the US colonial enterprise and sought to go back to the Spanish times to create this homogenous idea of Puerto Ricanness built on a 19th century trope called the Great Puerto Rican Family, in which this idea was that everyone belonged to the Puerto Rican nation. But when you look at it carefully, it is a deeply hetero, patriarchal discourse articulated by the white elites in Puerto Rico. And so that is what is being articulated in the 30s and later incorporated in the 50s. So absolutely, my book was in response to this myth of Puerto Rican delicate, because in that 30s generation it was the idea that we had inherited certain traits from the indigenous, from the African and from the Spaniard. But when you read the text, there are deeply racist texts that articulate ideas that the indigenous was. We inherited our fragility from the indigenous, our unruliness and. And our laziness from the African, and that we inherited that bravery from the Spanish. Right. And so this was this clear racist articulation of what a homogenous Puerto Rican identity should be. And so I am consciously going against that narrative, and I'm not the first one, but I was careful that I wanted to articulate my work in relation, intention and trying to shatter those ideas that ties to this notion of many Puerto Ricos, which is really interesting that you mentioned Gil Joseph's approach, which is tied to geography. And I'm thinking also of Mexico, profundo and whatnot. But what I was thinking with the multiple Puerto Ricos is that we experience Puerto Rico differently depending on our own sort of positionalities. And I think that for me became really clear after Hurricane Maria.

And I'm also borrowing some of this from my colleague and my partner in life, Aurora Santiago Ortiz, who has written about how after Hurricane Maria, you had people that had power generators and were eating lobster, while you had other people that were dying because they lacked access to potable water and electricity. Electricity. And so in a place like Puerto Rico, which is. It's 100 by 35 miles, it's not so much about geography, although geography also plays a role in the ways that Puerto Rico has been racially stratified, class stratified, but it's also about your own sort of positionalities and you experience Puerto Rico in many different ways. And so I guess that also that ties to, to my own conception. So I am drafting this sort of history of Puerto Rico, but I'm not thinking about this as the history of Puerto Rico, the national history.

That's why for me, the a national history is important, because I'm offering an interpretation of those multiple Puerto Ricos. And it's a Puerto Rico that is deeply tied and meets, mediated by my own subjectivities as a working class, light skin, cisgender man from Aguadilla, now in the diaspora. And I think that for me it was really important to think about what that meant, also educated, etc. And so I've been this year in Puerto Rico on a research leave and I've only gotten to confirm this idea of the multiple Puerto Ricos and how people experience it depending on their own positionalities even more acutely than when I was writing the book.

[00:36:08] Speaker B: You know, here I can't help but again return to Jesus Colon's vignette about Puerto Rican in New York, because he starts that story by talking about how he was first captivated by these words in his grade school textbook, we the People. And he quickly learns as a child that he is not included in we the People because he tries to play checkers on the seats of some club with or on the stairs to some club with his white teacher. And someone comes up and tells him that he can't be playing checkers with this person because he is Afro Puerto Rican, his teacher's white, so he quickly learned that he was not part of we the People. But then later on in the story, he reclaims the meaning of we the people in some ways as being the working class, they were the people. And part of me wants to wonder, wants to ask if something similar is going on. When you're talking about the great Puerto Rican family. I'm wondering if you think that you are actually trying to write the history of the great Puerto Rican family, but in a way that reimagines it for very different purposes than what people in the 19th century were doing.

[00:37:28] Speaker C: Yes, I think that I had not thought about it that way, but I think that I am definitely writing a history of another family in Puerto Rico, which is a working class class, black femme trans family in Puerto Rico, because I think that they also. So it's this sort of tension of who gets to write, who gets represented in the text. And so in these ideas of the great Puerto Rican family, it was always highlighting that sort of patriarchal figure of the father.

And I am not interested in that. I'm interested in documenting it as something that happened historically and that has been deeply influential in the ways that intellectuals tied to the state have crafted an idea of Puerto Ricanness.

But I am mostly interested in documenting people like Jesu Colon and documenting people that have been relegated outside of history textbooks. And so, yes, I think that. Absolutely. I think that I am writing a history of the great Puerto Rican community because I think it transgresses this idea of the family.

And so it could be the great Puerto Rican community. And I think that, you know, Jesucalon is crucial because I'm also, and this is where my book departs from earlier sort of textbooks of Puerto Rican history or national histories of Puerto Rico, because the diaspora was not imagined as part of the Puerto Rican nation, in part because I think the diaspora is racialized as an Other because of its proximity to black communities in the United States.

And so there's a sense of crafting them as others, as this foreignness to them. But for me, it was crucial to include the diaspora as part of our conceptualization of the Puerto Rican nation or a Puerto Rican nation.

[00:39:39] Speaker B: That's great. And then, Jorrell, lastly, you've been thinking about and reading and writing about Puerto Rico and Puerto Rican history for your whole professional life. And in some ways you've been living it for much longer, longer than the time that you've had a professional life, both in Puerto Rico, in Aguadilla and San Juan, and then in Connecticut, and even in white New Hampshire and now Wisconsin. So you've been doing this and thinking about this for a long time. And I'm wondering if in the process of researching and writing Puerto Rico a national history, if anything you learned surprised you. Given the fact that you've been doing this for so long, did you still find yourself able to learn new things about the nation of Puerto Rico?

[00:40:26] Speaker C: Absolutely. I think that there was a lot of self reflection in the process. But I must say that what I had to do in order to write this book was to not learn new things, but to unlearn a lot of the things I had been taught in graduate school about writing. And it ties back to this conversation that we were having on public history and reaching other audiences. So for me, it was a learning opportunity to unlearn a lot of the things that I was taught in terms of how to write, how to think historically and what things matter and what things don't.

I often joke that this book, one of the most liberating things that I had from this book is that I could not care less about what my colleagues were going to be thinking about the book when it came out. I was more interested in what my grandparents, my aunts, my family members were going to think about the book. And so that was very liberating. It's also very privilege to say because I already had the tenure book and so it allowed me to do that. But I think that also, you know, going back to this question of the diaspora, it really taught me about the centrality of the diaspora. And having grown in Puerto Rico from two weeks, because I was actually born in a military base and then brought to Puerto Rico two weeks after until I left to do my PhD.

It really taught me a lot about the centrality of the diaspora. And one of the things that really struck me is that the first works of history were not written of Puerto Rican history, were not written in Puerto Rico, but in the Spanish diaspora. The first work of literature, El Ribaro by Manuel Alonso, was published in Spain, not in Puerto Rico. The Puerto Rican flag was actually unveiled in New York City as part of the Cuban Revolutionary Party's Puerto rico section in 1895.

And so just to think about the centrality of those Puerto Ricans that have been forced to live abroad. And so that for me was really eye opening because I found myself writing this book in the vaibang, as Jorge Loani calls it, the coming and going of Puerto Ricans. And so it really allowed me to reflect about the centrality of exile and diaspora and being away in order to think about the Puerto Rican nation.

[00:43:09] Speaker B: Jor El I found that last set of thoughts really inspiring and I just want to thank you for taking the time to talk with us at Writing Latinos. And thank you so much, and good luck to you with the book on anarchism. Can't wait to read it. And finally, everyone listening, I want to urge you to go pick up your copy of Puerto Rico A National History. You will not regret it. Thank you.

[00:43:32] Speaker C: Thank you so much. It's been such a privilege to be in community with you.

[00:43:48] Speaker A: Thank you for listening to season three of Writing Latinos.

We'd love to hear your suggestions for new books that we should be reading and talking about. So drop us a line at geraldopublicbooks.org that's G E R A L D oublicbooks.org this episode is brought to you by Public Books. It was produced by Tasha Sandoval. Our music is City of Mirrors by the Chicago based band Dos Santos. You can follow us on bluesky, Instagram and X to receive updates about season three of Writing Latinos. I'm Geraldo Cadava and we'll see you again soon.