[MUSIC - “City of Mirrors,” Dos Santos]

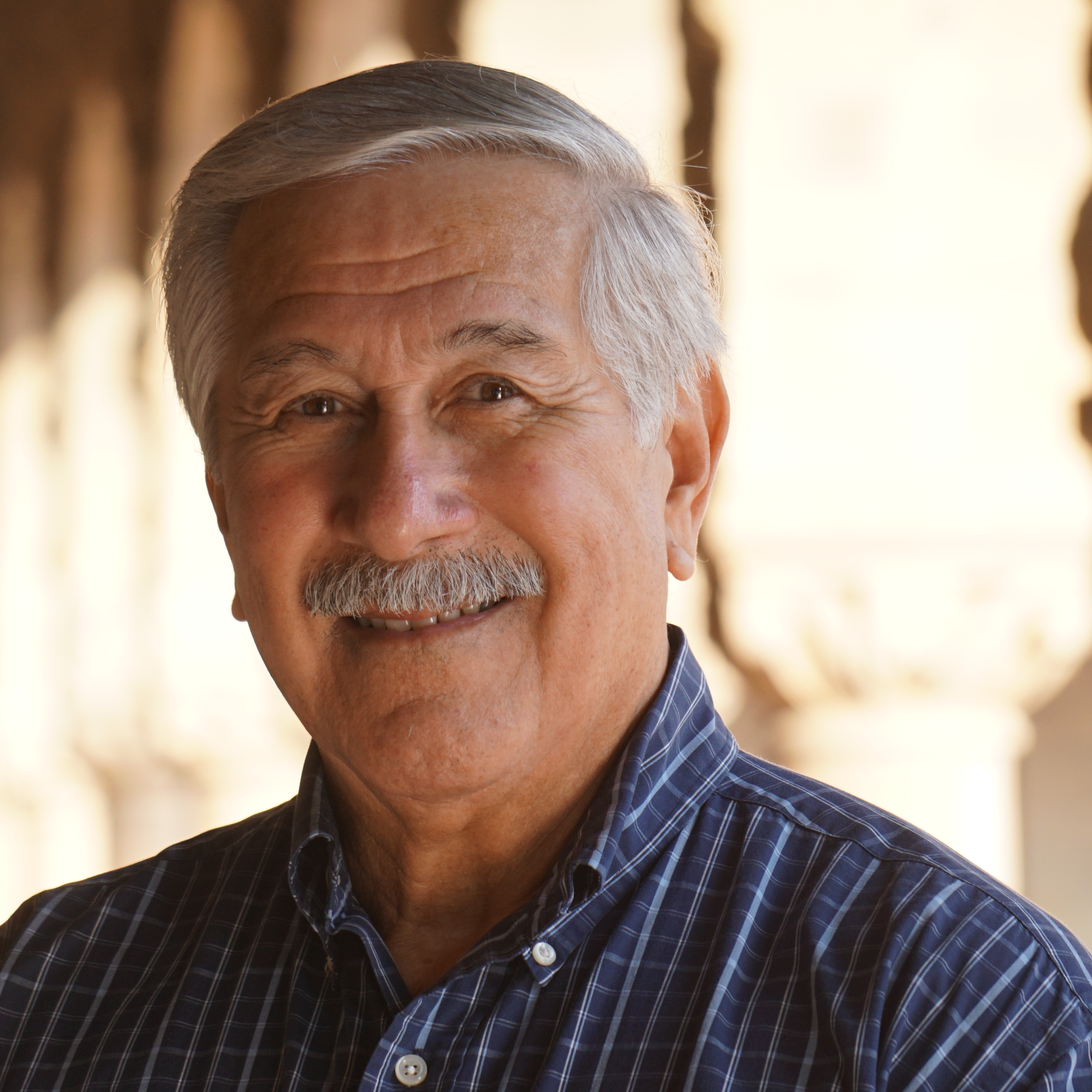

Hi, my name is Geraldo Cadava, and this is Writing Latinos, a new podcast from Public Books.

Latino scholars, memoirists, novelists, journalists, and others have used the written word as their medium for making a statement about latinidad. We’ll talk to some of them about how their writing illuminates the Latino experience. Some of our episodes will therefore be nerdy and academic, while others will be playful and lighthearted, all all will offer offering thoughtful reflections on Latino identity, and how writing conveys some of its meanings.

We’ll publish a new episode every two weeks. If you like what you hear, like and subscribe to Writing Latinos wherever you get your podcasts.

Now, for the show…

[MUSIC - “City of Mirrors,” Dos Santos]

I am delighted to talk today with Logia Garcia Pena, professor at Tufts University in the Department of Studies in race, colonialism, and diaspora. Garcia Pena is the author of three books. The first is the Borders of Dominicanidad: Race Nation and Archives of Contradiction, and then two published in 2022– I mean, it's amazing what a year you had last year. The first is Community as Rebellion: a syllabus for Surviving Academia as a woman of color published by Haymarket Books. And the second is Translating Blackness: Latinx Colonialities in Global Perspective, published by Duke University Press.

Thank you so much for joining me, Lorgia. I really appreciate your time.

Lorgia: Thank you for inviting me. It's truly a pleasure.

Lorgia: And Lorgiaa, why don't we start actually with your appointment at Princeton, where you'll be both in the Department of African American Studies and the Efron Center for Studies of America. What kind of opportunities do you think being in, in this new kind of institutional arrangement will allow you? How might it shape your research over the next few years?

Lorgia: So I am an interdisciplinary scholar and all of my work and all of my teaching moves between and back and forth and in vaivén, multiple fields. So I'm curious, and I'm also excited to see. The conversations that come out of different disciplines.

I am hopeful also for these conversations. I think we need to have more work that kind of breaks the disciplinary barriers because for a lot of the questions that many of us are pursuing, it's hard to do so from one discipline. So, I think that, within black studies, generally in African American studies, more specifically, the book has potential to expand and add to an expansive conversation about global blackness.

So I'm really excited to see what colleagues and people read it from, from Black studies, think of it and how they add to it, how they critique it and how can I grow for the next book from those critiques.

Gerry: Translating Blackness is a terrific and important work of scholarship. I mean, I think more than many things that I've read, it really tries to wrestle with the meanings of latinidad and Blackness together and really expands the frame far beyond the United States to include places like Italy. So I really can't recommend it enough to anyone who might be listening to this. And in the book, there are a few key concepts that I think it would be helpful for anyone listening to understand, and I'll name three of them. One is translation. Another is hegemonic blackness, and a third is contradiction with diction italicized.

Lorgia: So I'll, I'll start from the end. And Contradiction is a term that I use in my first book in the borders of Dominicanidad to think about the ways in which dictions literary works, performative works, narrative, even texts, are, appear in archives and in textbooks and are sanctioned at times by the state. And what I proposed in the first book is to read in contradiction against those normative, um, hegemonic versions of truth. And so when I was grappling with this book, which took me a good nine years to write, I was trying to think together about blackness, Latinidad, in the context of a world in which we tend to separate the struggles for immigrant lives from the struggles for black lives.

And I wanted to hold those two experiences together and think deeply, not only, about the people who identified as black Latinxs, and the sites and locations that we tend to imagine and sites of black Latinidad, but also their epistemologies, the ways in which these terms and ideas have come, come to exist from the 19th century to the present. So it was, it was a lot.

It was, it was one question, but it was expansive. And so when I was thinking about this, this work I had the, the fortune of having friends and colleagues read various versions of, of the manuscripts and I was in conversation with George Lipsitz at some point and he mentioned, you know, I don't understand why you're not bringing back contradiction into this work.

You know, this is a very useful concept. You introduce it in your previous book and it's just helpful for the work that you're doing here. And it was, it was really an aha moment, you know, really early, I'm talking, you know, six, six years ago or so, that helped me really piece together some of the ideas that I have in, in Translating Blackness.

And a lot of times I describe Translating Blackness as a sequel to the borders of Dominicanidad, in great part because as I was beginning to do research for translated blackness, I was also doing Footnotes and conclusion and light editing for the Borders of Dominicanidad.

And at some point it's like one book started to bleed into the other and I said, it’s time to stop, it’s time to move, to move on. But, but the questions that animated the book definitely influenced how I approached my research, particularly in, in, in Italy and specifically around citizenship and, and undocumented communities.

So there are multiple concepts that I I bring into how I think about blackness in this book. One of them is vaivén. Which you haven't mentioned, but it’s a really important one, and in fact, it's something that I originally had in the title of the book and, as editors do, that one that was cut.

I guess it was too long of a title. But it really helps me think about the comments and goings of the experiences of blackness and… The premise of the book is, how do we think together about colonialism, migration, and blackness in this moment? And how do we, uh, engage with the ways in which the nation and the world are reproducing multiple and new forms of exclusion and anti-blackness?

And for me, centering it on black Latin is critical because black latinidad helps us see coloniality through Blackness. It really does. When you think about the experiences of people who identify themselves as black latinx, they're for the most part migrants or descendants of migrants, but they also have, they carry with them multiple forms of colonialisms, right?

You, you're looking at the history and the legacies of European colonialism in Latin America, but you're also looking at US colonialism. And then confronting all of that with, for example, in places like the United States with internal forms of coloniality. So thinking about the ways in which colonialism, migration, and anti-blackness intersect in this moment, there is no better place to do that than from the, from the experience and the epistemologies of, of black latinidad.

Gerry: I would love to hear you talk a little bit more about hegemonic Blackness and what you mean by that.

Lorgia: Ah, hegemonic…

Lorgia: So what I mean about hegemonic blackness is the ways in which there is one dominant way in which we, meaning the world, understands black experiences, black truggles and black histories. And for the most part, that experience is mediated by the United States, by anglophone literature and cultural production. So if you go anywhere in the world and, and you look for images of black success people are going to be thinking about Obama or maybe Oprah.

And, and so what, what does that mean for the global South and for Black people from the global south? This to me is sort of key and critical to the work I'm trying to do in this book, but it's also the hardest thing to grapple with because it requires scholars in the US to understand that two things can be true. Tthat you can be as a Black person experiencing the cost of anti-blackness every day and dealing with facts like the police may kill you. And that's very true and very tangible. And at the same time, you can be an agent of empire in the way in which you move in the world, or just by virtue of carrying an American passport.

And so I am asking questions that are difficult to grapple with and that require us to sort of get out of our comfort zone and understand that in order to truly do transnational conversations well, we need to understand that there are hierarchies and there are power dynamics that influence even the way academic work gets deployed in the world.

And so, what does it mean for people in, let's say Latin America, to talk about anti-blackness by using the hashtag Black Lives Matter. It means multiple things, right? It gives them a a platform rom which to speak to a larger audience and put things into context for the world. But at the same time, it can create erasure. And so I'm interested in bringing attention to this tension and this dynamics and figuring out a better way forward.

Gerry: Let's, uh, linger on that point about duality for just a minute through the figure of Frederick Douglass, who I think you use to great effect in the book, as someone, who has, uh, as you put it now, has been a kind of victim of anti-blackness in his daily life, but for a period in the 1870s was also an agent of the American Empire when he was helping the United States explore the possibility of annexing the Dominican Republic. What does it mean to take this person that we're so familiar with and to understand him in this other context?

Lorgia: I think it, it, it brings attention to the complexities of being a minoritized person and eventually minoritized citizen of an empire in relationship to the world. And you know, reconstruction is a really important moment for how Black Americans are thinking about themselves in relationship to the world.

It's a moment in which the promise of colorblind citizenship is entertained. And we had not yet seen the heartbreak of this promise not being fulfilled. And so when Fredrick Douglas goes to the Dominican Republic as an arm of the US Empire and walks around the Bay of Samaná and meets with folks and creates his opinion about Dominicans, two things are happening:

He's seen this place as a potential site for Black humanity, and he's looking at race and race relationships in the Dominican Republic as operating differently than the United States. Less hierarchical from his, from his eyes, right? There's a moment where there's a mulatto president, there's a mixed race light-skinned, Black president at the moment, which in the US context was an impossibility in 1865. So he's seeing this and his, his mind is racing and he's going, okay, well if we make this state, then we guarantee two things. We guarantee that this, that this country progresses, and we also allow for these people to have American citizenship, which is powerful in the world.

And what would that mean for voting power? So he's thinking about black citizenship, but in the process of thinking about Black citizenship and thinking of himself as a carrier of US citizenship for the first time, he is also invested in this project of expansion for the first time.

And this is the same Douglas that 10 years before is saying no to expansion, right? No to imperialism, because imperialism means at this moment in the, in the 1850s, enslaving more people. So in, in a post sort of 1865 moment, he's, he's full of hope and he's thinking that this might work. Now he sees that it doesn't later on, and that's why he defends Cuba from annexation station and he defends Haiti from annexation…

But in this brief moment, his work and his words in relationship to Latinidad had an impact on how the politics of Latinidad versus North Americanness shape how Black, specifically Black Americans relate to Latin America. And what we see post Fredrick Douglas and, and my colleague at Tufts, Kerry Greenidge, just published this amazing, uh, book on the green keys.

What we see is, is this wave of African American men, for the most part, who are powerful, who are linked to the state serving as ambassadors and also extracting heavily from the local resources and acting very much following the same structures of American Empire.

So it's complicated and convoluted and hard to digest, but it's also human. And I think it would really help us to think through Douglas and Douglas’s contradictions in relationship to Blackness and Latinidad, that it would really serve us to look at it as an example of how we got to where we are right now.

But also in relationship to projects like diversity and inclusion, because to me, the way in which he was sent to the Dominican Republic, he's the only Black man in this commission that is sent, right? So there is also this way of producing Blackness that really resonates with the kinds of projects we see in the seventies and eighties that lead to the mess that is diversity and inclusion at the moment.

So it's, it's a project of tokenization that does not lead to actual political enfranchisement for Black people.

Gerry: So I couldn't help but thinking about the 1619 project, which Nikole Hannah-Jones opens up with this description of a tattered American flag hanging in front of her childhood home.

And that was about how her Veteran father still believed in this project of democracy, American promise and inclusion within the United States, but a lot of your actors aren't really arguing for inclusion within a particular nation state, but instead are fighting for recognition and equality and freedom for Black people all around the world.

Lorgia: Yeah. I think one of the examples of a middle ground for that would be Arthur Schomburg, who I write about in the second chapter.

I would argue that for Schomburg it's at both and situation, right? We want to assert our access to citizenship and we also want belonging. We also wanna be part of a nation without a nation. And I find his moment, um, to be really critical for, for both critiquing the nation, but also understanding that it is impossible to escape it. In a previous moment with Douglas and Luperónwho are operating in the 19th century, this is the height of nationalism, right? This is the moment in which a lot of nations are being built. You know, the Italian nation is being born, nations all over Central America are being created.

So, so the nation becomes the ideal to strive to. The idea that humanity could be represented fully by a state. And so if you are someone who has been fighting for that inclusion, whether, you are like Luperón, you are a military man, and someone who's been linked to the independence movement, uh, you want to insist on this possibility of the nation, as the the site of freedom, as the site of inclusion that which will allow you to fully be. But when it comes to the United States Nation, it's tricky, because it's a nation that was created at a time in which slavery was legal, right? And so what you have, really, is not a true independence and project of citizenship for all as you see in other countries. What you see in the United States is, is a change of masters from the British to the Sons of the British, right? And so there there is really very little change. And so I think the contradiction is more stark for minoritized and indigenous and Black people, especially in the United States, to be able to buy into a nation that did not ever not only include them, but I think sell them, as full human beings.

And I think there is a moment that sort of extends through the 20th century of believing in the nation and buying into patriotism, and buying into the idea of the constitution that never really was intended for people like us, but thinking that perhaps now it can be. I think that there is a desire and then there is also in many ways a hesitancy to see the possibility that the nation is a failed project, that it will never actually include us. Because if we think about that in those terms, then what else is left? How do we, how do we conceive of ourselves vis a vis other people. And I think that's something that a lot of folks are grappling with at the end of the 20th century especially.

Gerry: Yeah. I'm glad you brought up Arturo Schomburg, because he changed his name from Arturo to Arthur, and I think many people have read the name change as a sign of how he had come to cast his lot with the African American community in New York and perhaps the United States more broadly. But I think what you're showing about him is that it's much more complicated than that. He's also the namesake, of course, of the most famous library and archives for African American history and culture. But, as you describe it in your chapter about Arturo Schomburg, he was creating an archive of global blackness as well, not just African American, New York. So, I think he, in addition to Douglass, those are both two good examples of kind of entirely reframing our understanding of these individuals.

Lorgia: Yeah, I mean, Arthur changed his name from Arturo to Arthur, and then eventually as we see from Francis Negrón-Muntaner work now, back to Arturo.

Um, and to me, this is a reflection precisely of one of the many multiple experiences of latinidad. How to pronounce your name in a new context. How to live in multiple linguistic codes. Imagine being Black and boricua at the turn of the 20th century in New York when there were no names for who you are, and also being an immigrant and also being from an island that now belongs to the United States. There are all these multiple layers of belonging and non belonging that he had to, he had to navigate to be seen and to move in the world, and the spaces that were opened for him to allow him to do the work that he wanted to do in the world, many of them were in Harlem, which was a neighborhood that was booming with amazing work through, precisely, by African Americans and Black, Caribbean people at the time. And so it really isn't a sign of his switching sides or going, no. It is a vaivén. It is a vaivén that Latinx people, particularly those of us who are immigrants or the descendants of immigrants, go through in our lifetime. Right? We change how we pronounce our names or how we engage with certain topics, and that is how we move in the world because that is how our experiences are developed and shaped by what's around us.

Gerry: In your book, women are central as both survivors of ongoing colonial violence and organizers and even soldiers developing strategies of resistance against it. So can you talk about how a politics of gender sits at the core of the story you tell?

Lorgia: The women that I write about are powerful. Um, they're duras, you know. I began to write this book thinking I was going to write a book about black Dominicana’s migration to Italy. And so from the con… the inception of this book, it was always about women. From the beginning of the book until, it's, to the end, I am looking for Black Latinas. I am trying to see them in archives that purposely silence them. So in the beginning of the book, in the first chapter, as I am engaged, Gregorio Loperón and Fredrick Douglas because I wanted to find Gregoria Fraser Goins, who was their goddaughter.

And it's one of the stories that is most dear to me in the book. It's really just a beautiful, beautiful story and, um, throughout the book, I want to think about the ways in which Black Latinas defy, defy colonial violence, defy the afterlife of slavery, defy the atrocities of migration and somehow find ways of belonging, of being, and of creating and co-creating communities of joy that really fight back against the state.

Gerry: So the second part of the book in particular, centers around women beginning with 196 and sort of ending in this moment and looking at activism, and looking at literary works, and looking at the ways in which bodies of Black women have been used by powers to enact violence, and how those acts of violence, reappear in this present moment. Um, so I'm sort of trying in many ways to reconjure that violence to make us see it, but also to make us see the totality of Black Latinas’ lives in the present. How that violence is often contrasted by acts of resistance.

[MUSIC - “City of Mirrors,” Dos Santos]

Gerry: Writing Latinos is brought to you by Public Books, an online magazine of ideas, arts, and scholarship. You can find us at publicbooks.org. (spell out). To donate to Public Books, visit publicbooks.org/donate.

Gerry: I have just a few more questions about Latino identity.

There are just a lot of conversations in the air right now about Latina Latino, Latinx, Latine identity and all the debates about it. And I have been thinking a lot lately about mestizaje, as many others have as well. And instead of one of your characters, Gregorio Luperón used the term raza mixta. And Luperón, by the way, was the president of the Dominican Republic for a brief period in the late 19th century, but he had this term raza mixta, and I wanted to ask you how this term relates to the concept of mestizaje and how it might even address some of mestizaje’s shortcomings.

Lorgia: I mean, is writing in the middle of the 19th century and he wasn't formed as scholar, he was formed as a military man. And he was the son of a Haitian woman and Dominican of probably European ancestry man. And so he himself grappled with the multiple racial and ethnic identities that made who he was.

And I think in many ways, he was very invested in citizenship precisely because this is a moment, and we see it a little later in Cuba, this is a moment in which citizenship is replacing race in the Caribbean, right? At least in the way in which Caribbean, Hispanic Caribbean identities specifically are being deployed.

So his concept of mixed race, and he uses the term raza mixta, is quite different from mestizaje in that it begins and ends with Blackness and with Black freedom. So that at the core of this identity that he calls for, is this idea that we are a mix of multiple races and, but all of this multiple races can only come to fruition because of the liberating work of Black people.

Um, he's also one of the first people to use the term Latino for the first time, and to think about Latinidad as a political project, unifying Latin American countries against US Empire. And we're talking, you know, 1867. So this is really, really early and I find him really interesting in the way in which he allows us to think about Latinidad before, before the narrative of that became sort of sanctioned by the Mexican state in the 20th century come to become hegemonic.

And you know, what I, what I tell my students when we talk about this and I teach a seminar on Black Latinidadthat I enjoy and love is, I am all for canceling

whatever you want to cancel. If you wanna name us oranges, I'll take it. But I also would like those critiques to come after we have enough historical perspective. Because I think if we understood that first came Blackness and then latinidad and that this term latinidad was created as an anticolonial term that was grounded on Black liberation.

If we knew that, if we knew Luperón’s work, if we knew Betanza’s work, perhaps we would not be calling for the cancellation of the term, but rather reminding people that Blackness has always been central to latinidad. And so my, my, my impulse in this moment and in this dialogue is to insist that we get enough historical perspective. And then if you still wanna cancel, go ahead, sign me up. Uh, but let's do so not because of the moment that we find ourselves in, and the ways in which some people have co-opted the term and changed it. But let's do it because we really are aware of the totality of that history, and I don't think we are. Because Latinx studies until very recently has not centered Blackness. It still doesn't center it. There are more dialogues. But we have failed as a field to understand the significance of Blackness and anti-Blackness in Latinidad. And I think the question should be: how do we, how do we fix this?

Gerry: I was thinking too, back to your book about your discussions of Afro-indigeneity or Black indigeneity, and that seems to also complicate a simple distinction between white Latinos and Black Latinos. So really the question is just what are your thoughts about this discourse about white Latinos and Black Latinos?

Lorgia: I mean, what I think, and this is, you know, what I also teach my students is that Latinx and Latinidad is not a race. It's not a race, it's it's other things. You know, it could be an ethnic identity. It could be a cultural identity. It could be a political identity, but it's not a race.

I resist when I, when I hear the phrase Black and Latino. It's another way of saying that we are not both, that you are either or, and that's simply just not true. So, so for me, again, these conversations need to be complicated more.

It's not that simple as Black and white or Black or white. Uh, it's are, are we, um, do we have commonalities because of histories of colonialism, because of language, because of histories of migration? We do. Um, but how do we, how do we disentangle those commonalities from the fact that not every Latinx experience is the same?

There being an indigenous person who identifies as Latinx is not the same experience as being a white Argentine, living in the United States. Those experiences are not the same, and yet there are moments of encounter, which is why so many of us continue to embrace the term, continue to name ourselves, uh, Latina, Latino, Latinx.

So I think, yeah, the, the invitation should be how do we complicate this conversation beyond a binary that honestly isn't useful for thinking about Latinidad.

Gerry: Finally, I have to ask because there was banter on Twitter about this a while ago. And you and I. Yeah, I know. Let's go to Twitter to like, tell us what kinds of conversations…

Lorgia: Are you asking me about flan? Cause apparently my most controversial tweet was about flan (laughter)

Gerry: (laughter) No. Although I did have flan two nights ago. That's not what I was gonna ask you (laughter). I'm teaching this graduate seminar on Latinx historiography and we read Laura Gomez's book Inventing Latinos, where she states very clearly that Latino only makes sense in a US domestic context and it doesn't make sense to use it other otherwise. I read that knowing that we were gonna be reading your book later on in the quarter and remembering conversations we've had about how you were doing research in Italy. I was thinking, man, I have to ask Lorgia about this because I, I would imagine she has something to say. So, I'll just ask: tell me your thoughts about whether Latino exists or only makes sense in a US domestic context, or whether it can extend, say, to Latinos in other places like Italy?

Lorgia: You know, when we think about things like, you know, uh, popular phrases like race is a social construct, which we have been hearing for like, I don't know, since I was in college… I would agree that the term Latinx, Latino, Latina, or Hispanic as we know it today and as it's, as it's being deployed, it's a product of the United States.

I would agree with that. Um, both in terms of US imperialism, which is what I talk about in the first chapter of the book, but also in terms of the populations in the United States of people who trace their ancestors to Latin America and who are either born here or came here as young people and name themselves that. And so I would concede that that's important and that we need to understand that history.

I would also insist that in this historical moment in 2023, we are in a moment that is radically different from 1965, and that Latinidad has traveled, and that there are communities outside of the United States that are naming themselves Latinos. And I am not, I, Lorgia, am not gonna go and tell them that they are not.

Because that is not my job. My job is, as a researcher and as a scholar, is to listen and take seriously what people are telling me that they're naming themselves. Otherwise, that project of telling people how to be or how to name or what to feel in relationship to race and ethnicity becomes colonizing. And I don't wanna do that.

What I have seen, and this is what I can share, is that newer enclaves of Latinx identities are forming in other global north countries. Places like Spain, places like Sweden, places like Italy that I write about. And that those people who are born there and their parents are from Latin America, are looking at New York and LA to come up with a language with which to talk back to the nation. To me, that’s latinidad.

So the, the short answer is for me, in this moment, and again, we need to be very specific about historical moments and situations. This is not 1965. If you asked me that question back then I might have a different answer. But in this political moment,and in this moment, uh, in which migration, Latin American migration has been diversifying from being almost the majority of migrants coming to the United States, to having now sort of a multi-pronged approach to migration that has been going on for a good 15 years… In this moment, Latinidad, to me, applies to the experiences, histories, identities of communities, of people who trace their ancestry to Latin America and live in the global north and consider themselves in the global north minoritized communities in relationship to Latin America and the nation they live in.

Gerry: I cannot resist one small follow up: For those who insist that Latino is a domestic concept and want to keep it that way, are there consequences for letting others into that conversation?

Lorgia: You know, I'm not a big fan of borders. And both in terms of national borders and in terms of bordering people's identities and bordering people's ways of thinking and engaging. I think we lose a lot, uh, in that process. I understand as a Latinx study scholar that there is a history and a history that I am very careful to teach my students and to understand of Latin American studies and Latinx studies being in intention in a lot of our institutions because of a tendency of Latin American scholars to wake up one day and say, Ooh, I do Latinx studies. So I wanna clarify that this is not what I'm calling for or what I'm defending.

I am talking about taking seriously the way in which communities are calling themselves. And so who am I to go to a community of women who are organizing themselves as Latinx women in Sweden and say to them, actually, you shouldn't be using that term because you're not from the United States. I think there is room to understand that identities are plural. And that the lived experience of Latinx people in the United States is going to be different than the lived experience of Latinx people in Sweden. I think that that is fair to say, just like we say that about other experiences.That is true. But what is also true is that there is a reason why they are naming themselves Latinx. And that reason has to do with the shared experiences of feeling and being excluded from the nation that they are being born into and also from the nation their parents come from. And I think that's what we share. And I would be sad to miss the opportunity to have those conversations across… because I think Latinx studies can grow tremendously from having those conversation.

Gerry: Thank you so much for your time. I really appreciate the care and thought you gave to the questions. Thank you so much. And everybody go read Translating Blackness.

[MUSIC - “City of Mirrors,” Dos Santos]

Gerry: Thank you for listening to this episode of Writing Latinos—

We’d love to hear your suggestions for new books that we should be reading and talking about. Drop us a line at

[email protected]

This episode is brought to you by Public Books. It was produced and edited by Tasha Sandoval. Our music is “City of Mirrors” by the Chicago-based band, Dos Santos.

I’m Geraldo Cadava. We’ll see you again next time.