Episode Transcript

Writing Latinos_S2_Luis Miranda_For Publish

Puerto Ricans need to make the final decision of what the island political status is going to be like. It's not going to happen without the U. S. listening to Puerto Rico and Congress listening to Puerto Rico.

My name is Geraldo Cadava and welcome to Season 2 of Writing Latinos, a podcast from Public Books. We're back for more conversations with Latino authors writing about the wide world of Latinidad. As always, some of our episodes are nerdy and academic, while others are playful and lighthearted. All offer thoughtful reflections on Latino identity and how writing conveys some of its meanings.

If you like what you hear, like and subscribe to Writing Latinos wherever you get your podcasts. And now for the show.

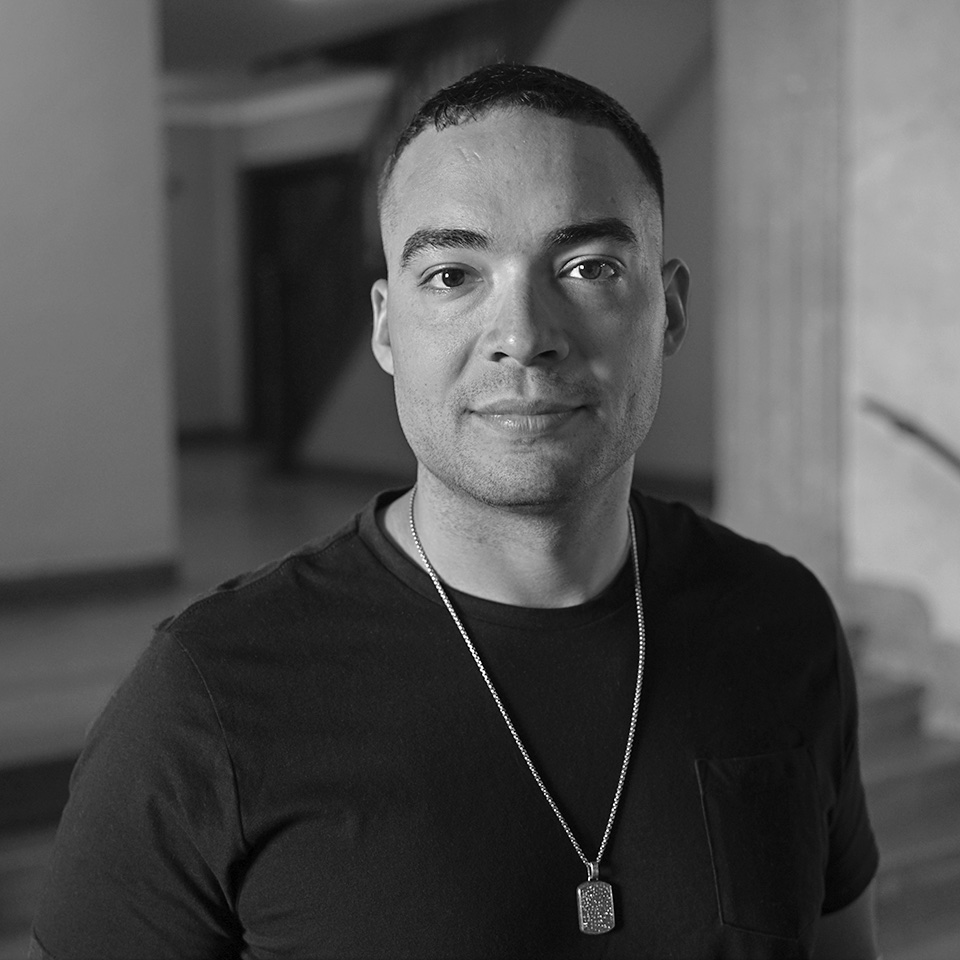

We are so lucky today to have Luis Miranda with us. Luis, how does one introduce Luis? He is a political strategist and consultant, a social justice advocate, an entrepreneur, a father, a husband, and for our purposes, an author. Luis is the author of a new book called Relentless, My Story of the Latino Spirit that is Transforming America, published by Hachette Books.

His son, Lin Manuel Miranda, wrote the foreword, in which he calls Relentless really three books in one. The first is a story of his father's life. The second is a story of Latino politics in New York City. And the third is The Latino Voter Nationally. In Relentless, Luis tells us that the single question he has asked for his whole career is, what do Latinos want?

And his book and our conversation about it will hopefully provide some answers. So thank you so much for joining us today, Luis. It's a real pleasure to have you. And it's a real honor being here with you. Thank you. And so, so many congratulations on your book. It really does feel like a summation of. The many, many different things you have done in your life, in your career, and I think the first thing I would like to ask you is a little bit about your career in Latino politics.

You've been doing this for a long time and in a city with a large Latino population that doesn't get written about as a Latino city or, or one of the hubs of Latino politics nationally. And you were in the thick, though, of figuring out how to mobilize Latino communities in New York from the 80s through the present.

And I think you're uniquely positioned to talk about how Latino politics in New York has evolved over the course of your career. So what's different now compared with when you began? When I began politics in New York City, uh, Geraldo, and first An honor, uh, to be here with you. You're, you're a real law author.

Uh, many, many books. Uh, but going back to your question in New York, back in the seventies and the early eighties, the Latino politics was really Puerto Rican politics. You were talking, um, To a monolithic group, they were overwhelmingly, uh, the vote in the city and little by little, Dominicans be gone. to car territory, increase their voting power, increase their numbers.

I think I'm very proud that I was part of that process because I believe that Latinos can ascend to power when the different groups can taste power and taste that they can do it and they have the help of somebody else. And now it's just a way more diverse Latino electorate, uh, with large groups of many Latino groups.

And with that also comes generational differences, now language differences, and ideological differences. So it is a much more complex political reality now that when I started back in the late 70s. I wanted to ask about now Latino politics nationally, because about a decade ago, you became involved with Latino victory.

And I was wondering if the work you've done for Latino victory has given you some way of comparing Latino politics in New York with Latino politics across the country. Because on the one hand, I could see organizing Latinos. locally in New York and nationally being kind of similar endeavors because New York is so diverse Puerto Ricans, Dominicans, Cubans, Mexicans, Ecuadorians, Venezuelans.

So as a politico in New York, you kind of have to understand these communities. But on the other hand, New York is not Texas. It's not Arizona. It's not Florida. It's not Wisconsin. So I'd love to hear you talk about some things you've learned over the past decade about Latinos in New York versus nationally.

I, I'll start by, by, by telling you that it is, I learned early on in politics, and that's why it's easy to move from New York elsewhere, somewhere else, that all politics are local. You don't need to speak with one voice to the Latino electorate. That is a myth. You need to speak if your path to victory, it's the electoral votes of Georgia, Wisconsin, and Pennsylvania.

You need to understand who are the Latinos who are in those three states and devise the strategies to speak to them. When I worked for the first time in Georgia 10 years ago. First thing I did was that I would have done in New York. I purchased a list of all Latino voters and it's Latino surname, it's Spanish surname, and you hope to get around 80 percent right when you get that list.

But when we started writing, texting people, communicating to people, 80 percent of the list was crap, was wrong, because no one in Georgia has spent a second and a penny in making sure they speak to the Latino electorate. So the basic tools that you need to begin to talk to that Latino electorate are not in place.

If I go in New York and I buy a list. I assure you that 85 percent of that list It's correct because we have invested, uh, in that political infrastructure. So part of the problem that I see of why Latinos are not understood and how we become a bit of an average of a whole bunch of different groups generationally, it's because there hasn't been any real investment in a political infrastructure that tries to figure out.

who we are. Yeah, yeah, that makes sense. And I guess, you know, that that would be a kind of commonality, even in places like Wisconsin, or even Arizona, or historically, heavy Latino communities, like in California, or whatever, I mean, polit politicians, political campaigns, still see Latinos through that lens, right?

I mean, they have a hard time knowing how to communicate to them. It, it, in the United States, we sort of see the world from the prism of black and white. All of a sudden, there is this large group, now 60 million, with real percentages, with elections are so close, that we are real percentages almost everywhere.

Yeah. They don't understand us, we're sort of an average, they have not developed Democrats or Republicans. They have not developed the political infrastructure to then begin to integrate. This very large number of people and a Latino victory, why I got involved and have been involved now for a decade.

It's because I believe that by creating a network of candidates, even when they don't win. By creating a network of candidates, you begin to create a political infrastructure of Latinos, of Latinos meeting each other, of Latinos working with each other, of Latinos teaching each other political tricks that otherwise would not happen.

Have candidates and campaigns gotten better at this? over the past 20 years that you've been involved in politics. We do have in politics the best of our community. It's like any other reality profession occupation. If you're not good, you'll disappear little by little because at the end of the day, the electorate is not stupid either.

Uh, and they know when someone is a joke, we just saw it in George Santos here, here in New York and throughout and throughout the country. So we learn a lot and Latino victory also makes sure that we nationalize races. I remember, and I tell the story in the book of a young Latina Puerto Rican, uh, who was running for DA in a small jurisdiction in Georgia, and she needed 30, 000.

All I had to do was to call my Puerto Rican friends, not even Latinos, my Puerto Rican friends, appealed to their nationality and said we can elect the first Puerto Rican female DA anywhere in the country. And we're going to get on a Zoom and we're going to meet her and we're going to have a conversation.

And in a Zoom, we raised the money she needed to begin to have that campaign. So having the possibility in a place like Latino Victory to nationalize racists, nobody would have met Deborah Gonzalez. from Athens, Georgia. Mm hmm. Without Latino victory being part of nationalizing her race. Yeah, that's a great point.

Your kind of political formation was really Puerto Rico, right? And I remember these stories that you told about showing up in New York in 1974, I believe, with your psychology books and books on colonialism. And, uh, I loved it. I mean, such a, such a vivid image, but, you know, Puerto Rican politics and how it intersects with U.

S. politics and colonialism. This is a very, uh, Difficult subject. It's tricky. It's tricky. Politics in Puerto Rico is no joke. No, it's no joke. And so, you know, you touch on it in your book, but I'd just love to hear, I think, listeners, you know, something I don't talk about too much, although I think about it a lot, is the statehood issue and territorial status.

But how is Puerto Rico? Puerto Rico is still a territory of the United States. You know, I mean, it seems to me a couple of years ago, it seemed like it was going to change. It seems like there's been momentum at various moments to actually have real binding plebiscites that force Congress to act. But here we are 126 years later without, you know, much having changed, not independence, not statehood, not a clear answer on this issue.

So what do you think? Where, where are we with us? Difference of politics in Puerto Rico and here, one of the, of the differences, it's that parties are attached to a final political status. a final political solution, uh, for Puerto Rico. So when you're trying to elect someone, a lot of the campaign focuses on that individual, but that's only 5 percent of the electorate, 10 percent of the electorate are going to change parties.

And what we have now seen in the last two elections in Puerto Rico is that people are beginning to get tired Of the same old, same old election after election and third party candidates that believe in independence, believe in autonomy. Some other that it's not Commonwealth or statehood are beginning to emerge as real political figures in the, in the island, but not powerful enough to win.

I believe that Puerto Ricans need to make the final decision of what the island political status is going to be like. It's not going to happen without the U. S. listening to Puerto Rico and Congress listening to Puerto Rico. One of the things, you know, I, I go to Puerto Rico often to see my family and all the philanthropic work that we, we do in Puerto Rico.

Something that it's becoming clearer in Puerto Rico. It's that the Democrats Republican, it's not as clear. clear cut as it was a decade ago. When you had the resident commissioner of Puerto Rico being a Republican and the head of Latinos for Trump, uh, the notion that many had that we will never get statehood because it will just be seven, uh, Democratic Congress members and two Democratic senators.

That's beginning to change a bit. Are you thinking about Jennifer Gonzalez? Is that? I am. I am. I'm thinking about Jennifer. Now she's running for governor. And I'm sort of giving a primary, uh, to the sitting governor in Puerto Rico, Pian Luisi, Governor Pian Luisi. In your book, you kind of recount some of the earlier moments of like peak, uh, independence activism with bombings and, and things like that, and kind of violent support for the nationalist cause in Puerto Rico.

But have, have you seen the conversation about the status of Puerto Rico, the status question? Have you seen it? change in the politics of that question change or are we kind of stuck? That's what I'm wondering. I mean, are we, are we kind of stuck or have you seen things change a lot? In, in, in the fifties and the sixties, when I grew up in Puerto Rico, there was a strong Puerto Rican independence movement, uh, in the, in the fifties, when, when my uncle created the, Puerto Rican Independence Party.

Who is this? Who's your, who's your uncle? Gilberto Concepcion de Gracia. I'm Miranda Concepcion. The independence movement was real. And what I have seen over the decades is that you have an entire generation of Puerto Ricans who have an affinity. For the American American citizenship. That didn't happen in my generation.

Even Luis Ferre, who created the pro statehood party, said that Puerto Rico was the patria and the United States was la nacion. So the one that you felt attached from heart was Puerto Rico. And there's this other entity. That is the nation that it's a U. S. But more and more, you have an entire generation of Puerto Ricans in the island who believe That they are American citizens, and that, and they are, but in my head, that's never real.

Uh, and that only statehood will give them all of the rights that an American citizenship have. Because if you travel 90 miles, you get them all when you get to Florida. Yeah. Why, why did you say that in your head, the American citizenship that Puerto Ricans on the island have is not real? Again, I'm Puerto Rican.

I, I, That's the patria. I will be Puerto Rican until the day I have, uh, the U U. S. citizenship is the passport that allows me to go somewhere. But if that passport said Puerto Rican citizenship, I will be totally content.

Writing Latinos is brought to you by Public Books, an online magazine of ideas, arts, and scholarship. You can find us at publicbooks. org. That's P U B L I C. B O O K S dot O R G. To donate to Public Books, visit publicbooks. org backslash donate.

Part of what interested me so much about the book was learning about your background in psychology too. I didn't know that. And you described something in the book that I think this conversation is reminding me about because I've heard, um, you know, this, you know, attachment to the United States or attachment to the passport or attachment to being an American citizen described as some sort of like colonial complex or something like that.

Or I think, did you call it in your book, like a Puerto Rico syndrome? What is the syndrome? When I came to New York, Remember, this is the early seventies. Yeah. Uh, so we're still in the first generation of Puerto Ricans. We call it un patatu. It's, you know, it's when you have some burst of emotion and you can scream, you could throw yourself on the floor.

You, it was that set of behaviors. That was called a Puerto Rican syndrome. It's sort of a hysterical reaction to something, but I figured anglo psychologists saw This brown people screaming and rather than use the usual terminology, uh, that psychologists use, they call it a Puerto Rican syndrome. I remember thinking, Oh shit.

Yeah, my family did that. And we all still do that. I, I didn't know that it was, it had a name. Uh, but at the end of the day, it's, it's really racism more than, uh, Yeah, totally. That is the patatu. That's the patatu. It's a patatu. Yeah, we call it a patatu. Le dio un bichipujo, un patatu. Se va a gritar como una loca.

You know, we have ways of describing it. But scientifically here, they call it the Puerto Rican syndrome. Oh my goodness. Yeah, that's amazing. But I want to talk about things a little bit closer to home now. I think, you know, a lot of what you had to say about being a father and that being your most important job, I think it resonated with me in part because, uh, you know, I have a 10 year old son and, uh, you know, I'm thinking a lot about my relationship with him and how to, um, you know, raise the best child that I can.

And so I drew a lot of inspiration about what from what you had to say about your first job being that of a father. And, you know, you're someone who seems to have really lived a full life and had a full career at the same time that you've, that you've been a father. And I remember some of these scenes.

I can't remember if it was when you were working for Mayor Edward Koch or, uh, Freddie Ferrer or David Dinkins, but these scenes of you kind of being in the office until three in the morning, waking up at five in the morning to do it all over again, Luce would bring your children to the office so you could at least see them for a minute.

But, um, those must've been hard trying times, but throughout it all, you've. managed to kind of keep family and being a father at the center of everything. So what's your advice about how to how to do this? First of all, you have to get a great partner. And you have to great have a great partner, because you have to be able with that partner to learn about what you missed.

and have an opportunity to hear from that partner their interpretation of what happened. And then you have, uh, your, your own. Uh, so many times I probably live vicariously. Things that happened to my children because I wasn't there, but Luz was there or Moondi was there. Remember Lin Manuel calls her Abuela Claudia in, in the Heights, but that's a real person.

It's the person who worked in my house and raised me and my sister. And then we brought her to New York and she raised with us it. Manuel. Yeah. Uh, so you, you first need that first account of what's happening, and then you, you have to always be open. My kids know, and everyone who knows me to this day knows that if my kids called me, I will stop whatever I have and I will answer the phone, and sometimes it feels rude.

But I always wanted them to know that the world will stop, even if what they had to say was una boberia. Being involved at some level, I believe it's key, uh, in kids. feeling that they are the number one thing in your mind. So continuing on about fatherhood, you know, you're not just a father of anyone, you are now the father of an international celebrity.

And that's, that's a kind of whole new phase of fatherhood in some ways, right? So It is, Gerardo. And constant in my mind. Sometimes I want to call someone horrible things because I believe they deserve to be called horrible things. And I don't because I'm Lee Manuel's dad. Because the story, it's always Luis Miranda comma.

Yes. Father of famous Lin Manuel Miranda. Right. So I am now, which was never a preoccupation in my life. Right. Now, I'm terribly conscious of curating. A bit my narrative as I talk to people, because it will all reflect a bit on Lin Manuel. That's so fascinating. I mean, that's like a different way of being a father though, than what, what you did for the first phase of Lin Manuel's life before he was famous.

You're parenting him in a different way. And also the role doesn't change at the end of the day, the kids are center stage. So now center, having them in center stage means a bit about how do you say what you say so that he doesn't badly reflect on your famous son. Wow, yeah, that's fascinating. Because one of the main themes In the book is just your role as a father and all of your children's lives.

And so it's really interesting to hear you talk about how your thoughts about being a father have changed over the past 15, 20 years. Sometimes I sent an email to myself saying what I want to say. And then I feel better and in the morning I delete it. That's a great practice no matter who your kids are.

I feel like it's kind of sending drafts and leaving it in the draft folder. That's a way to save so much heartache. Another kind of point of connection between you and Lin Manuel that I found fascinating in the book is I should, I should like, uh, fully confess that I have taught a class on Hamilton the musical at Northwestern three times.

I know you have. Yes. I've taught that class. And one of the themes I pick up on a lot is this kind of ambition and preoccupation with death about, you know, why do you write like you're running out of time? Sometimes I imagine death so much it feels like a memory. you wrote in your book, a chapter about your own funeral.

My wife has not read it. Oh, she hasn't. She has not, and she refuses to read it. She thinks it is morbid. I said, I'm doing that for you. You will be grieving so much that I have now facilitated that last chapter by telling you exactly which songs you're going to play. Okay. So I have so many follow up questions.

Okay. So first of all, reading your chapter about your own funeral made me think about like, huh, maybe, maybe like death and thinking about mortality has actually been a through line, uh, of the family's history. And is that something that you maybe passed along to Lin Manuel or? I'm sure I have. I'm going to be 70 in several months.

You're a young man. Yes, but that's not the story of the Miranda man. Ah. And, and in fact, My dad had quadruple bypass when he turned 62. My grandfather had a massive heart attack when he turned 62. So when I turned 62, I went through all kinds of tests. Oh. And I was, Lin Manuel was filming Mary Poppins in London.

Yeah. And I was in London and my wife sent me a picture of the letter that I got from the doctor. Sort of one of those very Trump ish letters. You have the best heart in the world. You're never gonna die. I've never seen a heart like this. It's beautiful. I've never seen a heart like this. Two weeks later, I had a heart attack.

Oh man. So if I worry a little bit about death, it's a little based in reality, but I am sure, uh, that is mortality. It's something that I have always been very conscious of. Mm hmm. And it's tied to ambition and all of the things that you want to do in life for yourself and your family because you are a man who has a lot to do in this world.

It is and you begin to feel like I don't have as much energy as before Or I need to do a little more exercise for the first time I have to stretch myself some more Uh so that I could behave a bit Uh, like I did, uh a decade ago Uh, but for me writing that chapter You Was encapsulating What's important to me?

Yeah and Believe me. I have told my family there's nothing in that chapter That they have not heard because everybody believes i'm a bit morbid. Uh since death. It's always, uh, part of, of, of my trajectory. Uh, but it's encapsulated. It is the music that is important to me. I know your soundtrack is amazing.

I mean, tell me a little bit about your soundtrack. What, why, what do those songs mean to you? It starts with being Puerto Rican. It starts with my favorite song of all times. Amanecer Borincano by Alberto Carrion. It's a Beautiful song that encapsulates for me being who I am. Then there are songs from the unsinkable Marla Brown.

I love that. Yeah. Because the unsinkable Marla Brown, I really saw that. When I was 10 years old, and it caused the incredible impression that, oh shit, you can move out of your circumstances. You really can aspire, and you just have to work hard to be in that other place where you want to be.

are part of Lee Manuel's book. And then I called, you know, Hachette told me I needed to call everyone that I, that I talked about in the book. I saw Alex Lacamoire, uh, who's a musical director in the heights of Hamilton, uh, fantastic, uh, genius. Uh, musical genius and he sees me at this cocktail and he said, I got your message.

No, don't worry. I even called your son to tell him that you deputized me to do the music at your funeral. And he was very happy. That was one less task that he had. Oh my goodness. That's amazing. That's amazing. I got to say the two songs I think that you chose from Hamilton were One Last Time and Yorktown and they're so different songs.

I feel like they're such different songs, the kind of tone of them and Yorktown, I have to say, I have a hard time imagining that playing at a funeral. Those, they are the moments in Hamilton that they always make me cry. Because there is a sense of we can win. We can have it all. We can create a new country.

We have these ideals that we won in the battlefield that for me are symbolic of the small and big triumphs. That we all have as migrants in this country that help us build up a better community and a better country and a better family and become the best version of who we can be in the United States.

So they are very, very different songs, but they encapsulate for me, Hamilton's story. That's very interesting. I mean, I think for me, it's dear Theodosia. And that's because I mean, my son was born in 2013 and Hamilton came out in 2015. So I feel like any parent of a young child listening to dear Theodosia is going to get weepy and tear up.

But it's interesting that what you say about one last time in Yorktown makes complete sense. And I'm also catching Based on the origin story of Hamilton, like someone who transcends his circumstances and what you had to say about Molly Brown transcending her circumstances and not giving up, I feel like there's this through line among the Miranda men too, about kind of transcending your circumstances to fulfill the best promises for yourself and for your country.

And I believe that legacy, it's important. It could be as simple as raising good humans. By raising good humans, we create good families, we create good communities to as big as changing. the American theater. I don't know if the book feels to you like a culmination of so many of the stories of, of your life.

And I mean, it's a culmination in one sense, but it's also a new birth in another sense, because the book will come out and thousands of people will read it. And that'll become a new moment in your story because people will be responding to what you wrote down. But I was just It was staggering to me to see all that you've done in your life, all of the kind of different arenas that you've had a genuine impact on and I really thank you for writing Relentless and I really wish you the best of luck with it and I hope to anyone listening out there that you will go pick it up and you won't regret it because it's just full of amazing stories.

So thank you so much, Luis. Gracias, Geraldo. It's a pleasure having had this conversation. Yeah, it's a pleasure to talk to you as well. Thank you. Thank you.

Thank you for listening to this episode of Writing Latinos. We'd love to hear your suggestions for new books that we should be reading and talking about. Drop us a line at Geraldo at publicbooks. org. This episode is brought to you by Public Books. It was produced by Tasha Sandoval. Our music is City of Mirrors by the Chicago based band Dos Santos.

I'm Geraldo Cadava. We'll see you again next time.